Testing with twins tells us you can’t pin performance on genetics

We know there’s no single winning formula for fitness. Some of us can transform strength and fitness with just a few weeks of exercise, others follow the exact same routine and see less dramatic results. Such idiosyncrasies have often been pinned on individual genetics, but a fascinating new study of twins suggests DNA has little influence on our response to exercise. Australian scientists recruited 42 sets of young, healthy, and sedentary twins (30 pairs were identical and 12 fraternal) assessing their endurance and leg strength before starting them on two three-month exercise stints. One stint involved 60 minutes of running or cycling three times a week. The other, 60 minutes of weight training three times a week. At the end of each three-month session, researchers reassessed participants’ aerobic fitness and muscle power. While most participants saw positive gains, the results varied greatly and even identical twins saw remarkably differing outcomes – suggesting results are not genetically-dependent.

What the scientists found particularly interesting was that if one of the participants responded poorly to the endurance training, they seemed to get increased benefit from the strength training, and vice versa. This shows that not everyone reacts to exercise in the same way, but there is an optimal exercise strategy for everyone.

The anti-aging secret that lies in our bones

Keen to maintain your youthful body and mind? Research into bone health and anti-aging provides more evidence that exercise could be key to maintaining muscle and brain health as time ticks by. It all comes down to a magical protein called osteocalcin, which is abundant in our bones. Gerard Karsenty has studied osteocalcin since the 1990s, conducting a series of experiments identifying how osteocalcin reverses age-related ailments. He has also found that osteocalcin increases the ability to produce the molecule ATP, the fuel that allows us to exercise. Regular exercise stimulates the production of more osteocalcin in our bones, which is secreted by osteoblasts (the cells that synthesize bone). “We know that people who are very active tend to have less of a cognitive decline with age than sedentary people,” says Karsenty. “With time, maybe people will be more aware of this connection, and think of their bone health as being just as important as other aspects of staying healthy.”

Could squats and star jumps slow vision loss?

Macular degeneration is one of the most prevalent causes of vision loss. It is estimated that about 10 million Americans suffer from the issue, so it’s no surprise that researchers have long been exploring how to alleviate it. Past studies have linked a healthy lifestyle with healthy vision, however, these have been based on self-reporting. Now, for the first time, researchers have hard evidence from the lab – albeit using mice. Scientists from the University of Virginia School of Medicine have found that exercise can reduce the overgrowth of harmful blood vessels in the eyes by up to 45 percent. An important reduction, as when these blood vessels get overgrown and tangled, issues occur such as macular degeneration, glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. While the study didn't delve into the exact type of exercise that will benefit your vision (directing mice to do anything other than cardio training on a spinning wheel would be difficult), it did highlight that the beneficial effects could be seen after just a very small dose of physical activity. The scientists aren’t certain exactly how exercise is preventing the blood vessel overgrowth, saying there could be a variety of factors at play, including increased blood flow to the eyes.

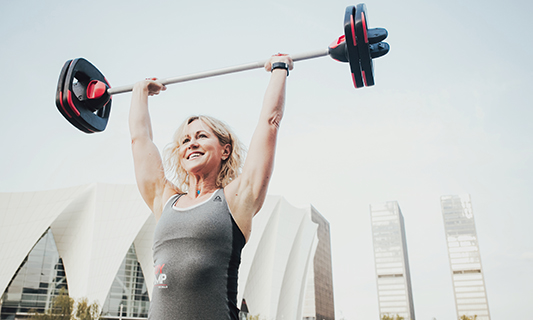

Lifting weights strengthens your nervous system first, then your muscles

Thanks to weight lifting monkeys we now have fascinating new insights into how your body responds to resistance exercise. These findings, which come from a new study published in The Journal of Neuroscience, detail how weight training affects the nervous system. Scientists trained monkeys to pull weighted handles each day, increasing the weight over 12 weeks. On each day they also stimulated both the corticospinal tract and the reticulospinal tract (the two major neural highways descending to the spinal cord) and measured the electrical activity in the arm muscles. They found the corticospinal tract didn't change during strength training. It was the outputs from the reticulospinal tract that became more powerful. This study highlights the neural mechanisms that contribute to increases in strength when weight training.